Most of us say that our pharmaceutical drug spending is soaring.

Not necessarily.

Prescription Drug Spending Facts

Yes, our prescription drug spending is up. But the reasons relate much more to our age and health than to prices.

1. Canada spends more.

When we look at average per capita out-of-pocket spending on prescriptions, in 2017, Canada ($144), Norway ($178), Korea ($156), and Switzerland ($216) spent more. In the U.S., the average was $143.

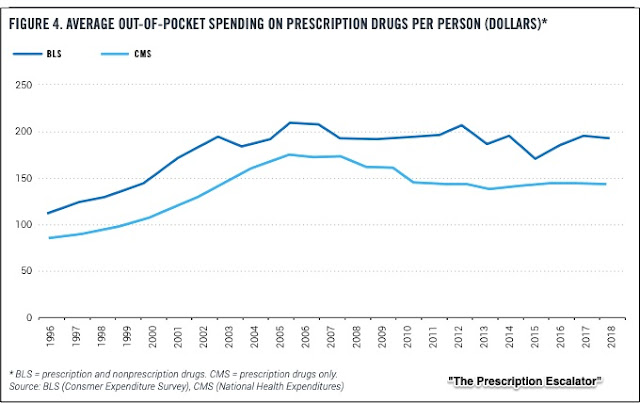

2. Prescription drug spending has been stable or falling.

Between 2013 and 2018: average household spending on prescription drugs was down by 11 percent according to the BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey:

Many baby boomers have begun to spend close one-third of their income on prescription drugs:

4. As we age, we buy more prescription drugs that cost us less.

Although we buy many more prescriptions, the out-of-pocket cost per prescription falls:

5. Our out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs is up less than for most other healthcare categories.

Second in a 10 item list, prescription drug spending was up 8 percent from 2013 to 2018:

6. People with fair and poor health pay less for each prescription.

The average out-of-pocket cost per prescription for a healthy person is approximately $15 while it’s closer to $13 for someone with poor health:

Our Bottom Line: Thinking at the Margin

Alfred Marshall was the first economist to look at the significance of the margin. Defined as where you start to use extra, the margin is where we decide if we want more of something. When you order another slice of pizza, you are thinking at the margin. Similarly, how fast you drive, how much you study, and whether you sleep later in the morning all involve marginal analysis.

For prescription drug spending, we’ve probably been looking at the wrong margins. Directing our economic lens to the extra spending we do as we age could provide more insight.

My sources and more: Thanks to Marginal Revolution for alerting me to The Prescription Escalator that was described clearly and thoroughly by economist Michael Mandel. From there, I took a look at OECD pharmaceutical spending data.

Ideal for the classroom, econlife.com reflects Elaine Schwartz’s work as a teacher and a writer. As a teacher at the Kent Place School in Summit, NJ, she’s been an Endowed Chair in Economics and chaired the history department. She’s developed curricula, was a featured teacher in the Annenberg/CPB video project “The Economics Classroom,” and has written several books including Econ 101 ½ (Avon Books/Harper Collins). You can get econlife on a daily basis! Head to econlife.