From the Wall Street Journal:

A behavioral economist knows about incentivizing exercise. But we need to start with my dishes.

For several years, I’ve listened to “page-turner” mysteries when I do the dinner dishes. In fact, the 14 novels in the Maisie Dobbs series were so good that I actually looked for extra dirty plates. Somewhat similarly, one reason I walk four miles each day is a late night (big) scoop of high-fat super premium coffee ice cream.

Temptation Bundling

Combining dishes with novels and walking with ice cream, I’ve been temptation bundling. Done alone, each activity has less utility (satisfaction or pleasure). I won’t enjoy the dishes and I feel guilty spending an hour or two with Maisie Dobbs.

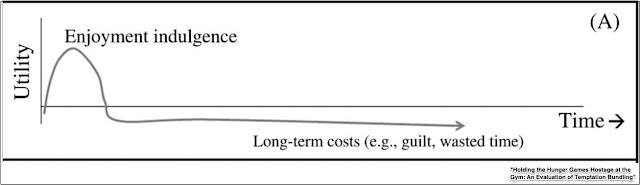

For a beneficial activity, quite the opposite happens. First we have the pain, and then the benefits:

Together though, the cost and benefit change. Because I experience less guilt, the long-term cost curve is no longer as low on the utility axis. Correspondingly, the “pain of execution” diminishes. For both, there is less cost and more benefit.

But, does it really work?

The Experiment

To see if temptation bundling had academic resilience, researchers divided 151 people who wanted to exercise into two groups. One group received iPods loaded with tempting page-turner novels that could be accessed only at the gym. The second group didn’t have the book incentive.

The results confirmed most of what we would expect. Group 1’s workouts exceeded the control group by 27%. So yes, temptation bundling did increase the frequency of the undesirable activity—the “should.” However, we should note that it didn’t kickstart a permanent workout regimen. After a temporary Thanksgiving break, neither group displayed “staying power.”

Our Bottom Line: Complementarities

As economists, we could say that we have been looking at demand complementarities. When the price of peanut butter decreases, our demand for jelly goes up. If I purchase a home, I will need new furniture. Similarly, temptation bundling creates demand complementarities between wants and shoulds. Each can incentivize more demand for the other.

So, returning to where we began, the answer to the WSJ question is to temptation bundle. Just figure out what guilty pleasure you want to combine with more exercise.

My sources and more: In The Washington Post, Penn Professor Katherine Milkman takes us to several commitment devices. Much drier, the academic formula for health interventions is described in this paper. Then, for a fast read, here is a brief summary of a flossing study. However, the best source that combined the academics and some fun was this Freakonomics podcast.

Please note that we’ve previously published sections of today’s post and our featured image is from Pixabay.

Ideal for the classroom, econlife.com reflects Elaine Schwartz’s work as a teacher and a writer. As a teacher at the Kent Place School in Summit, NJ, she’s been an Endowed Chair in Economics and chaired the history department. She’s developed curricula, was a featured teacher in the Annenberg/CPB video project “The Economics Classroom,” and has written several books including Econ 101 ½ (Avon Books/Harper Collins). You can get econlife on a daily basis! Head to econlife.